Process vs Outcome

While results may take time, generally speaking good process leads to intended or “good” outcomes while bad process leads to undesirable or “bad” outcomes. As an example, if you consistently burn more calories than you consume, you will lose weight. One or two days of this won’t really have the desired result (losing weight) but one or two months of this almost certainly will. Weight loss is probably one of the more poignant examples where the process takes some time to manifest, hence using the example.

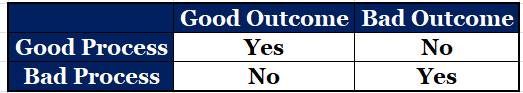

As a general rule, the relationship between process and outcome can be thought of as a simple matrix like so:

Unfortunately, speculation (trading/investing) is a game where it can take a very long time for the above matrix to materialize. How long might it take? Years.

A few caveats: A good process with too much risk eventually leads to ruin regardless of how good the process. A bad process with virtually no risk might avoid ruin forever.

In terms of the amount of risk necessary to cause ruin, it depends. In the extreme, if you bet everything every time you cannot have any outcomes go against you and, considering I know of no methods with 100% win ratios, you’re inevitably doomed. To summarize, too much risk can turn a good process into a bad process. In thinking about this, I realize good/bad processes live at both the strategy level (more below) and the risk level and that bad process in terms of risk supersedes any strategy process. If this is a bit confusing, keep reading.

Selling options naked short is probably the poster child bad process leading to good outcomes strategy (for a while). Option sellers can go years without a hiccup until the lights go out in a matter of hours. For the many years leading up to a blowup (in a bad way) things look peachy.

The other side of the equation is probably trend following. Trend following (with appropriate risk) is basically the opposite of selling options and can spend years without a good outcome considering the aggregate. Stated another way, trend following tends to spend years in a drawdown which, by most accounts, is a bad outcome (during the drawdown).

If life were simple, that would be it, but life is not so simple. To make matters worse, there is some sequence of events that will derail every strategy. Thus, in my opinion, the determination of good and bad process becomes a matter of possible and probable.

In theory, the right way to deal with possibility and probability involves math and statistics. This seems right but I believe it is, in fact, wrong - let’s explore why.

Say I use statistics to identify a high probability strategy which has a 100% win ratio. Cognizant my Spidey senses should be going off finding a 100% win ratio, my results will be based on my sample window (aka the timeframe I used in selecting data for my statistical analysis). While I might find something that worked with 100% effectiveness in the testing period, if the future doesn’t look almost identical to the lookback window, I’m very likely in big trouble (financially speaking). The larger point is that statistics can only be trained on the period of observation and, if the future doesn’t look like that window, the statistics can be incredibly detrimental to your financial health. Math can be dangerous if viewed as infallible.

In practice, I believe possibility and probability need to be viewed in common sense terms. As an analogy, I often think of a person walking in an open field which has one or more landmines. If that person walks long enough, they will eventually step on a land mine leading to a “game over” situation. The number of mines can be roughly approximated using common sense. So, if you use a ton of leverage, that means more market land mines. If you expect the future to look almost identical to your lookback window, more mines. If your strategy is not proven out in the actual practice of other successful traders, more mines. And so on. The more market land mines you have, the higher the chance of a bad outcome which inevitably results from bad process.

Bottom line, process vs outcome is a gray area and is actually probably more art than science which needs to consider the above in conjunction with your goals, temperament, reality, etc. The combination of all of these things should help to identify the “right” path.

In thinking about the above, I realize an underlying assumption is that ruin is unacceptable which may not be true for everyone - if your goal is to make a fortune, you will probably have to be willing to risk ruin. I also realize the lookback window game has no end. Relying on 100+ years of success might be just as susceptible to error as a 3 month statistical lookback. I suppose the differentiation comes down to the underlying logic. For example, cutting losses as a means to avoid ruin makes logical sense as opposed to say relying on statistical odds to save you. Similarly, trend is the only quantitative method I know of that will benefit from the future not looking like the past - if a market rises for 100,000 days in a row, a simple trend model designed to capture such a phenomena will capitalize on that whereas other statistical methods will break down since we will be in unchartered territory. Of course, cutting losses and trend following are not without their issues - as stated above, years of good process can lead to bad outcomes.

As a final note, they say that writing things down helps with both understanding and clarity of thought. In writing this post, I came to see process in strategy and process in risk level as related but separate things ultimately realizing that process in risk level is the most important since too much risk can sink any ship.

What a can of worms!